Years active

1923 – 1952

Stage Name(s)

Gladys Bentley, Bobbie Minton, Fatso Bentley

Category

“Bulldagger”, Butch

Country of Origin

USA

Birth – Death

1907 – 1960

Bio

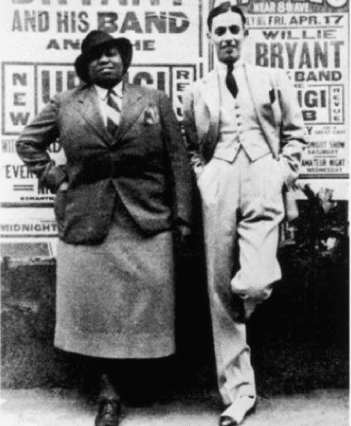

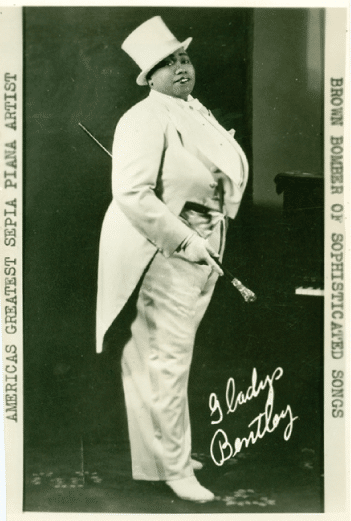

Gladys Bentley was an inspiration to many as a prolific African-American, out and proud lesbian, and bawdy gender bending entertainer during the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance. She was a robust 250 pound woman with a deep, growly voice making her adept as a blues singer and a powerful pianist. Wearing her signature white tuxedo and top hat, she appealed to audiences whether straight or gay, black or white. Gladys transgressed sexual, social and gender boundaries to become a symbol of LGBT and women’s liberation that was fifty years ahead of her time.

Born in Philadelphia, PA on August 12, 1907, Gladys Bentley was the eldest of four children to George L. Bentley and Mary Mote of Trinidad. Her parents wanted the best for their children and encouraged them to act properly and look respectable. Gladys did not like wearing dresses and preferred to wear her younger brother’s clothing. Bentley knew who she was and what she wanted from an early age. She was determined to use her amazing voice, witty lyrics and enormous musical skill to make a name for herself while living the life as she wished.

At 16 years old, Gladys left home to pursue her dreams in New York City to live as a cross-dressing bulldagger, the moniker for butch lesbian, and to become an entertainer in the rhythmic heartbeat of Harlem. After World War I ended in 1918, Harlem became a booming hotbed of entertainment. At this time, prohibition made way for speakeasies and illegal bars that quickly populated various neighborhoods. This underground scene is where jazz music and sexual liberation were born. Gladys felt inspired within this world to freely express herself and be celebrated for it. Initially she started out singing and playing piano for rent parties. Her notoriety grew quickly as she improvised indecent bawdy lyrics to the popular songs of the day. In the intimate atmosphere of the club, Bentley could get up close and personal with her audience. She flirted with the ladies and made them blush with her “sex-quisite’ songs. She would glide from table to table, giving each party their desired request. She never had to refer to a manuscript as she had a thousand spicy songs memorized and she never seemed to run out of them. Her sultry deep alto voice and very dapper strong appearance kept her crowd mesmerized and entranced. Audiences couldn’t get enough of her non-apologetic performances and she went on to become one of the most well documented queer black entertainers to come from the early part of the 20th century. This is perhaps because she pushed the envelope on gender, class and race through her performances and how she chose to live her life on her terms.

She was one of the highest paid black women in the US during the height of her career she reportedly made $125 a week. This afforded her to dress as a dapper gentleman in her signature white tuxedos, bow ties and top hats. During her heyday, she once owned a Park Avenue apartment equipped with servants and lived in luxury. Gladys had it all, including allegedly marrying a white woman in New Jersey in the early 1930s.

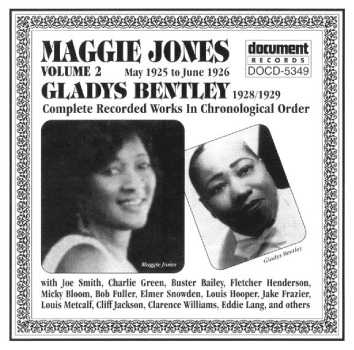

In 1929, Okeh Records signed Bentley and she recorded eight solemn songs, about women done wrong by their man. In contrast, her live performances were bawdy instead of bluesy, with Bentley playing up her butchness and making the audience blush with her boldness.

Bentley’s claims to fame were performing at the Apollo Theatre, the Cotton Club, and the notorious Harry Hansberry’s Clam House—one of New York City’s most well-known gay speakeasies. Located in the center of Harlem nightlife in an area called “Jungle Alley, a stretch of 133rd street between 7th and Lenox Avenue, The Clam House entertained a notable gay and lesbian clientele. There are various accounts of how she got her big break at Harry Hansberry’s Clam House. Some claim that the Clam house was looking for a male piano player, so Bentley dressed as a man. Others claim that she was already “mannish” and got the job because she was simply a very talented musician. She also was well known for headlining act at the Ubangi Club (1934-1937) where she created her own musical review with a chorus-line of male dancers in women’s drag.

The Great Depression, economic downturn and repeal of Prohibition took its toll on Harlem making it too dangerous for gays and lesbians to perform in the once queer-friendly nightclubs of Harlem. In 1937, Bentley packed her bags and moved out west to find work as an entertainer in Los Angeles. Gladys played at the notable gay club Joaquin’s El Rancho, until the police stopped her from performing in men’s clothing.

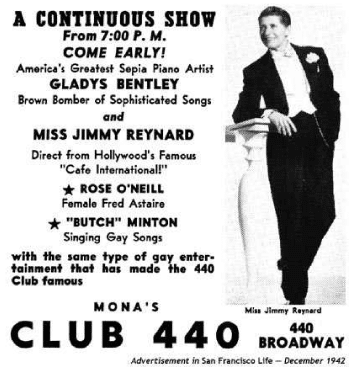

In 1942, she moved to San Francisco and performed regularly at the famous lesbian bar Mona’s Club 440 which was known to host popular male impersonators of the time. Billed as the “Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs”, she wore men’s attire when she performed there. After World War II ended in 1945, her career took off again as more gay clubs opened up and she was billed as “America’s Greatest Sepia Piano Player”. Despite her popularity in San Francisco, Bentley’s appeal began to decline so she returned to Los Angeles to live with her mother. She did perform regularly at the Rose Room in Hollywood, CA until 1952 though it is not known if she continued to dress in men’s attire during the perilous McCarthy era of the 1950’s.

In 1945 she was signed on the Excelsior label, which specialized in African-American artists and marketed to multiracial audiences, to record heterosexually themed blues songs as the political climate did not support her lesbian inspired tunes of years past. At the end of her career she recorded ‘Easter Mardi Gras” & “Before Midnight” on the Flame label and in 1958 appeared as a guest performer on the Groucho Marx’s’ television show.

In 1960, Gladys Bentley died suddenly from the flu in Los Angeles, CA at the age of 52.

(Submitted by: Ken Vegas, Washington, DC)