Years active

ca. 1914 – ca. 1940

Stage Name(s)

Bert Whitman

Category

Male Impersonator

Country of Origin

USA

Birth – Death

ca. 1888 – 1964

Bio

Said to be “the best male impersonator of the race” and the “ebony Fred Astaire”, Bert Whitman was considered one of the best male impersonators of her day. Born around 1888 to a former slave turned poet, scholar, and preacher, Whitman began performing at an early age. Whitman and her three sisters formed a troupe of performers and toured the United States beginning in the 1900s. While it is unknown exactly when she began male impersonation, the Whitman Sisters troupe consistently performed in vaudeville theaters from the 1900s to the mid-1930s to great critical and financial success. Whitman primarily performed with her sister Alice Whitman, dancing to and singing romantic and suggestive songs together. Bert Whitman excelled at tap dance, which was largely viewed as a male dance style at the time. In the mid-1930s, Whitman’s vaudeville bookings dried up. Whitman turned to other venues at this time, including the Club Vendome in Buffalo, which was known for its hospitality to Black and White lesbians. Whitman and her sisters used their platform as performers to fight racial injustice amidst the deep racism of the Jim Crow era. They advocated for Black theater ownership and chipped away at segregation in theaters. Additionally, Whitman used male impersonation to portray sophisticated Black men in order to combat negative stereotypes of Black men in minstrel shows. The Whitman Sisters troupe performed throughout the country primarily to Black audiences and occasionally to White audiences. Whitman and her sisters formed the longest-running and highest-paid act in Black vaudeville and were referred to as the “Royalty of Negro Vaudeville.”

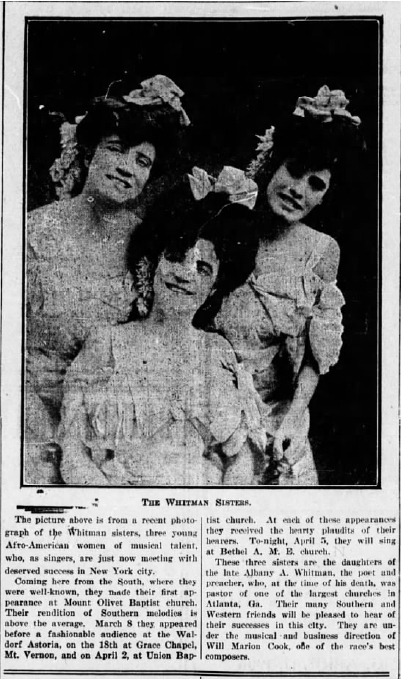

Bert Whitman was born in 1888 in Lawrence, Kansas, as Alberta Whitman. Whitman used “Alberta” as her offstage name and “Bert” as her stage name. Whitman’s father was Albery Allson Whitman who had been born a slave in Hart County, Kentucky, in 1851. He was a poet, scholar, and preacher. His most notable poem was an epic about a fugitive slave, Not a Man and Yet a Man, published in 1877. He wrote a poem entitled “Freedom’s Triumphant Song” for Colored American Day at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. He was dean of Morris Brown College in Atlanta as well. He was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church for many years and led congregations in Ohio, Kansas, Texas, and Georgia. Essie Whitman, Bert Whitman’s older sister, claimed that their father was a first cousin of renowned poet Walt Whitman. However, Albery Whitman’s great-niece, Ernestine Lucas, disputed this claim and traced the family’s lineage back to Port Tobacco, Maryland, instead. Bert Whitman’s mother was named Caddie Whitman. She was born in Kentucky in 1857. She read Albery Whitman’s poetry aloud in public. Historians and scholars have suggested that Caddie was White. Unfortunately, not much else is known about her. Whitman had two older sisters, Mabel Whitman and Essie Whitman, a brother, Caswell Whitman, and an adopted younger sister, Alice Whitman.

Bert Whitman learned to dance, sing, and play music from an early age. In Kansas, her father taught Whitman and her sisters to dance as a form of exercise. Her father had learned these dances growing up as a slave in Kentucky. Bert Whitman and her sisters sang, played guitar, and danced to spirituals alongside their father as he preached. Whitman also played piano at church socials. Around 1898, Whitman and her sisters began to perform for other churches and in other concerts. Whitman and her sisters were discovered by a theatrical agent around this time when performing at New York’s Metropolitan Baptist Church. Whitman and her sisters claimed that their father was against their performance career, but historians, scholars, and Ernestine Lucas have disputed this claim. The early history of Whitman is shrouded by such inconsistencies. Lucas explained that Whitman and her sisters likely “made up” narratives to form “a good dramatic show business story.” Nevertheless, it is clear that Whitman and her sisters continued to perform throughout the 1900s. One scholar noted that Whitman and her sisters may have gotten their start in vaudeville on the Orpheum Theater Circuit and attempted to pass as White. Nevertheless, they primarily performed on Black vaudeville circuits and at churches throughout the decade. Their mother served as their manager until she passed away in 1909. Their father had died in 1901.

After the passing of their mother, Bert Whitman’s older sister, Mabel Whitman, assumed the management role. Mabel Whitman was one of the first Black women to manage and continuously book performances in Southern theaters. By 1910, Bert Whitman and her sisters were highly successful. By 1916, Whitman and her sisters had added extra performers to their troupe, which then totaled ten performers. By 1917, Whitman and her sisters had purchased the Dunbar Theater in Columbus, Ohio, and were managing it. The theater featured vaudeville and movies. Whitman served as the movie operator for the theater. Additionally, Whitman helped manage the troupe’s burgeoning financial success as treasurer of the troupe. Whitman wrote the music for most of the troupe’s shows as well.

There is no clear beginning to Whitman’s male impersonation career. In the 1900s and 1910s, Whitman and her sisters performed minstrel acts in blackface, possibly at the insistence of theater managers. These acts may have had an element of resistance to them as they parodied minstrel tropes. Whitman may have started her male impersonation career in these minstrel acts to even out the gender imbalance of a mostly female troupe. If true, Whitman continued to do male impersonation long after she quit minstrelsy sometime in the 1910s. Whitman was referred to as “Bert Whitman” by 1914 and by 1919, Whitman was consistently doing male impersonation. Whitman told the Baltimore Afro-American in 1929, “One night about seven years ago…a boy, who sang one of my songs, dropped out…Boys were awfully hard to get and as I had written the song, I knew the song and could sing it, so I rigged up an outfit and filled his place. As a boy I went over big, bigger than in anything I’d done before. So, a boy I stayed.” Regardless of the specific date, Whitman had endeared herself to audiences as a male impersonator by the 1920s.

The 1920s were a decade of continued success for Whitman and her sisters’ troupe. Whitman had a hit with her own song, “Think of Me Little Daddy,” in 1920. Whitman said of the song: “I wrote that piece of music during the World War, when my sweetie was leaving for the battlefront in the East.” No recording of Whitman singing the song exists; however, Wilbur Sweatman’s Original Jazz Band recorded the song in 1920 and Jimmie Lunceford and His Orchestra recorded it in 1939. By 1924, the Whitman troupe included twenty performers. In 1925, Whitman and her sisters purchased a fifteen-room mansion on Chicago’s south side. In 1926, Whitman, her sisters, and the troupe were presented to President Calvin Coolidge at the White House and were given a tour of the living quarters by First Lady Grace Coolidge. By 1929, the Whitman troupe reached its largest number ever with fifty performers.

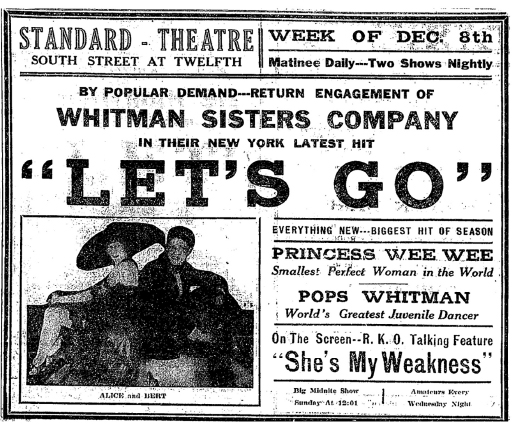

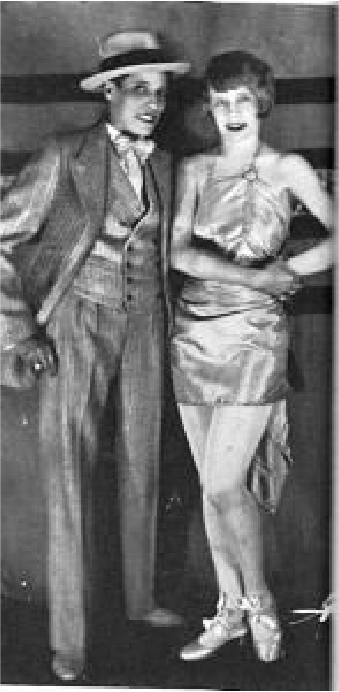

During the 1920s, the structure and content of Whitman and her sisters’ shows solidified. The whole show ran around seventy-five minutes through most of the 1920s; however, the act was shortened when the troupe performed in movie theaters in between movies. Effectively, the Whitman troupe formed their own vaudeville bill–each performer did a short segment, generally a song, dance, or comedy skit. Bert Whitman generally was in a few segments during each performance. Whitman consistently did male impersonation throughout the 1920s, both dancing and acting in male attire. Whitman was best known for dancing with her sister, Alice Whitman. Bert Whitman would generally introduce her sister, who would then perform a solo dance. Bert Whitman would then return to perform a “boy-and-girl song-and-dance” number backed by a chorus. Bert Whitman frequently did solo numbers, where she showcased what she termed “flash dancing,” or “legomania,” which involved throwing her legs in jiggly movements in many different directions. She would occasionally lead the show’s finale with this dance style. Additionally, Whitman sometimes had comedic scenes with Princess Wee Wee, a three-foot-tall singer and actress who was a longtime member of the Whitman troupe. Whitman frequently changed costumes throughout a performance as well. The Pittsburgh Courier remarked that Whitman had “more changes than Greta Garbo.”

Throughout the early 1930s, Whitman, her sisters, and the troupe continued to perform to great success as they had in the 1920s. Despite the Depression, audiences continued to turn out to see Whitman and her sisters perform. In 1933, the Whitman troupe was credited with saving the box office of the Lafayette Theater in New York, which had been floundering for eight straight months prior to their engagement. However, with the decline of vaudeville and Mabel Whitman’s decision in the mid-1930s to focus exclusively on managing two child stars in the troupe, Bert Whitman’s regular performances came to a halt. 1934 was the first year without a Whitman troupe tour.

Without regular vaudeville bookings, Bert Whitman brought her male impersonator act to the Club Vendome in Buffalo, New York, in 1936. She managed the show there as well. The presence of Whitman’s male impersonation at the Vendome is significant because historians Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline D. Davis have noted that the Vendome was hospitable to Black and White lesbians in the 1930s. Whitman also managed her sister Alice Whitman and Arthur McMullen, an MC, during this time. In 1937 and 1940, Bert Whitman returned to the vaudeville stage briefly. After 1940, Whitman retired from performing. In retirement, she lived with her sisters in their fifteen-room mansion in Chicago, moved to Arizona, and then returned to Chicago to live with her sisters once again.

Bert Whitman was married at least three times. Her first husband was Maxie McCree, a young vaudeville dancer. The two were married in or prior to 1920. McCree tragically drowned in 1922 at the age of 23. Whitman wrote a poem to mourn his passing entitled “In Memory of Maxey” that was published by the Chicago Defender in 1924. Whitman must have remained close to McCree’s family after his death, as she wrote a poem entitled “Little Mother” to mourn the death of McCree’s mother in 1933, which appeared in the Defender the same year. Whitman married her second husband, Abdeen Ali, in 1925. Ali was a member of the Whitman troupe. Whitman’s third husband, Sherrod Smith, was a clarinet player from Ohio. They were married sometime before mid-1936 and divorced in 1937. Their divorce received splashy coverage in the Cleveland Call and Post. Whitman may also have been married to Franc McClennan, a comedian in the Whitman troupe, as reports emerged of their impending marriage in 1929, but no confirmation of that marriage survives.

Bert Whitman was known for wearing traditionally male clothes off stage. She told the Baltimore Afro-American in 1929: “I went in for typically mannish styles because it was good showmanship, and now the public demands me in that type of clothes. I’m not Bert Whitman to them unless I’m as near a man in looks as a girl can be.” When she spoke to Atlanta Daily World reporter Norman E. Jones in 1932, Jones said that Whitman wore a “white suit, satin lapels on the coat, tall hat and jeweled cane that she handles so well.”

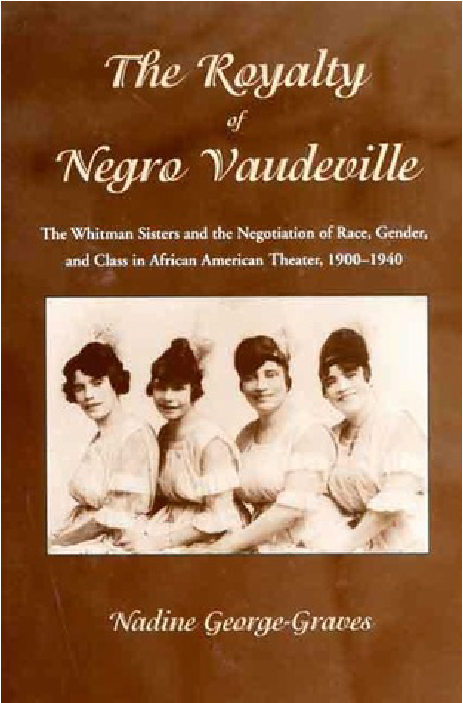

Many scholars and historians have analyzed the way Whitman performed and interacted with gender. Scholar Annemarie Bean argued that through male impersonation, Whitman created a sophisticated image of Black maleness that stood in direct contrast to White minstrelsy. Bean contended that Whitman was able to break stereotypes of Black men and women through male impersonation. Theatre scholar Jocelyn L. Buckner argued that Whitman complicated gender and sexuality through male impersonation and by dancing with her feminine sister to romantic and suggestive songs. Buckner described Whitman’s performance as “resistant drag” that reconstructed and glamorized Black masculinity in hopes of encouraging imitation of this Black masculinity in other cultural venues. Buckner contends that Whitman and her sister were able to do so because as sisters and as women, audiences did not view them as a romantic couple or a threat. Buckner highlighted that Whitman was able to succeed as a tap dancer because she was a male impersonator and tap was considered a male dancing style. Scholar Nadine George Graves has argued that Whitman and her sisters frequently challenged contemporary expectations of Black women and that the Whitmans had great agency over and experimented with their identities.

Whitman and her sisters frequently used their platform as famous entertainers to call attention to racial injustices. In 1929, Whitman spoke to the Pittsburgh Courier about the need for more Black theater owners. She said that “conniving white owners who squeeze the public and refuse to give performers a living wage…demand all and give nothing.” She hoped that more Black theater owners would book shows for Black audiences, showcase the talent of Black performers, and give Black performers equitable treatment. The Whitman Sisters troupe also tried to avoid playing to segregated audiences and would request that Black audience members be seated in the parquet and dress circle areas of theaters, yet they stopped short of demanding full integration, as audience members were still grouped by race within these sections.

Whitman and her sisters were well known for their charitable work for AME churches as well. Wherever the troupe stopped, they would pay a visit to a local AME church and donate at least $10. The troupe helped at least twelve churches pay off their mortgages through donations and benefits. For example, in 1927 the Whitman troupe set up a tent and performed for two weeks to raise money for Grant Memorial AME Church in Chicago.

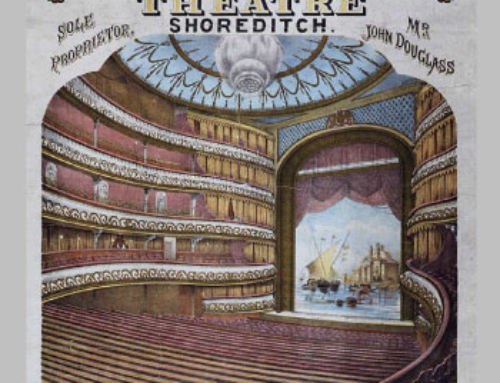

Over the course of her career, Whitman performed in numerous venues throughout the country, mostly in vaudeville. She most frequently performed on the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA) circuit but made appearances on the Keith and Proctor, Poli and Fox, Pantages, and RKO circuits as well. Whitman performed in large cities (such as Chicago, New York, and Atlanta), smaller cities (such as Beaumont, Texas; Hot Springs, Arkansas; and Shreveport, Louisiana), and as far west as Arizona. Whitman performed primarily for Black audiences. However, the Whitman Sisters troupe occasionally held midnight performances for White audiences.

Whitman made a significant impact on Black vaudeville. Not only was she a highly successful male impersonator, but she helped incubate Black talent. She helped train numerous young Black performers in the Whitman Sisters troupe, which was known for its inclusion of young performers. The Whitman Sisters troupe also gave jobs to many Black performers who went on to later success such as Count Basie and Jackie “Moms” Mabley.

Whitman has had an impact on contemporary artists as well. Margaret Morrison, a dancer, playwright, actor, choreographer, and scholar has created two pieces that were inspired by Whitman. In 2009, Morrison created “In Search of the Whitman Sisters,” a dance tribute to the Whitman Sisters, for the Barnard College Tap Ensemble. In 2013, her play “Miss Bert Whitman Meets Dyke Astaire” was given a staged reading in New York City. In 2012, Whitman was inducted into the International Tap Dance Hall of Fame with her sister Alice Whitman.

Whitman died of a prolonged illness on June 19, 1964, in Chicago. She was buried at South View Cemetery in Atlanta.

(Submitted by Andrew Forschler, Bowie, MD)