Years active

618-907 A.D. Tang Dynasty

Stage Name(s)

Lao Sheng (old man), Xiao Sheng (young man), Wu Sheng (warrior)

Category

Male Impersonators

Country of Origin

China

Birth – Death

N/A

Bio

With great acclaim, we begin Drag King History with the first known presentation of male impersonation which occurred during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) in Chinese Opera.

Origins of Chinese Opera predate the Tang Dynasty yet it is during this era where this art form became more organized. Chinese Opera evolved from folk songs, traditional dance, and distinctive dialectical music culminating into one performance on the stage. Research by Zeng Yongyi, a scholar of traditional Chinese theatre, cites women began to play male roles around the mid-Tang, a little later than men playing female roles. (Zeng 1977).

The rise in popularity of Chinese Opera during the Tang Dynasty was because it became more organized under the reign of Emperor Xuanzong (712–755), the son of Empress Wu Zetian. He founded Liyuan, the Pear Garden, which was the first school in Chinese history to train musicians, dancers and actors. The performers created what is widely considered the first organized opera troupe in China and were called “Disciples of the Pear Garden”. Performances were held in the royal courts mostly for the emperor’s personal pleasure.

One of China’s four great folktales, The Butterfly Lovers, can be traced back to the late Tang Dynasty. This legendary tale of two lovers is played by a man and a woman, the latter who dresses in men’s clothing as disguise. Upon her reveal it is discovered they cannot marry due to familial circumstances. He falls ill and dies from heart sickness and she falls into his grave where the two lovers eventually turn into butterflies. This classical romantic tragedy is considered the Chinese Romeo and Juliet though predates it by almost 1000 years. It is still a wildly popular opera today keeping male impersonation at the helm.

So why was male impersonation accepted during the Tang Dynasty ?

Here are some of the findings:

– China’s one and only female Empress, Wu Zetian, reigned during this era from 690-704. Despite being controversial due to her gender, she was an effective ruler. Thanks to Wu’s father, she learned to read, write, play music, and speak well in public. Her intellectual abilities made her a successful leader laying the foundation for the international golden age as the Tang Dynasty was regarded. (Mark 2016)

– Empress Wu instilled Buddhism as the nation’s religion which brought gender equality. She commissioned the Longmen Grottoes in Henan Province, China which include more than 2300 caves and niches in a stretch of limestone less than a mile long. Within it stands the Royal Cave Temple, also known as the Kan Jing temple.

– Because of Empress Wu’s reign, women were permitted to wear men’s clothing in public. This allowed ease in their daily tasks and way of life. (Rong 2005)

– Terracotta statues that still exist today show women on horses playing polo. This reflects their status in society during that era. (Benn 2002)

– China has a rich history of women warriors. It was Princess Pingyang who secured the establishment of the Tang Dynasty through sheer grit, smarts & determination. Her father, Li Yuan, decided to overthrow the government with the aid of his children. She was the only child who succeeded in their mission. (Zhao Chenxi 2011)

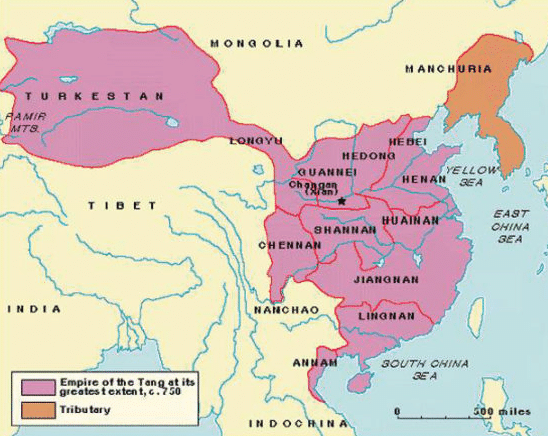

– Wu reopened the Silk Road ending in the city of Chang’an which was China’s capital city and place where she ruled. This brought tremendous cultural influence with the likes of Arabs, Indians, Syrians, Persians etc. Hence society during the Tang Dynasty was more open and accepting, and China emerged as one of the greatest empires in the medieval world.

Thanks to the research by scholars Yongyi Zeng, Chou Hui-ling, and Yeong Chen, we have strong evidence of male impersonation during the Tang Dynasty and why these strong, courageous women proliferated.

(Submitted by Mo B. Dick, Los Angeles, CA)