Years active

1955 – 1969

Stage Name(s)

Stormé DeLarverié

Category

Male Impersonator

Country of OriginUSA

Birth – Death

(c.)1923 – 2014

Bio

Stormé DeLarverié was a legendary male impersonator, international icon, LGBT community activist and “a self-appointed guardian of lesbians” (1) in New York City. She performed as a male impersonator serving as the Master of Ceremonies and show director for the renowned Jewel Box Revue from January 1955 to September 7, 1969.(2)

Stormé was born in New Orleans to a black woman and a white man, and due to her mixed race, was never issued a birth certificate. She never knew her birth parents. She was fostered in the Midwest where she was raised with two older foster siblings. Dates and exact locations are either unknown or kept private.(3) We do know from an interview with photographer, filmmaker and gay activist, Avery Willard, that Stormé used December 24, 1920 as her birthday.(4) This birth year does not correspond with the year of her high school graduation in 1942; other records suggest that her birth year was 1923. (5) We are not thoroughly certain of the exact year of her birth, and, just as the year of her birth is a mystery, so too are the details throughout her life off stage.

We do know that as a bi-racial child, she wasn’t white enough nor black enough; she endured taunting, bullying and abuse from kids both black and white. There was a story Stormé shared about being beaten up and left hanging on a fence by one leg, and that leg injury haunted her all her life.

And we know that she loved other women at a time when it was criminally, professionally and socially punishable. Like most LGBT people in her day, the past conjures up painful memories, and seemingly the best solution is to leave your family and past behind to start anew. (6) This is why creating a wholly accurate, definitive biography for Storme is challenging.

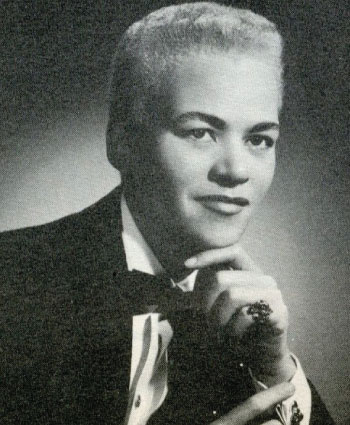

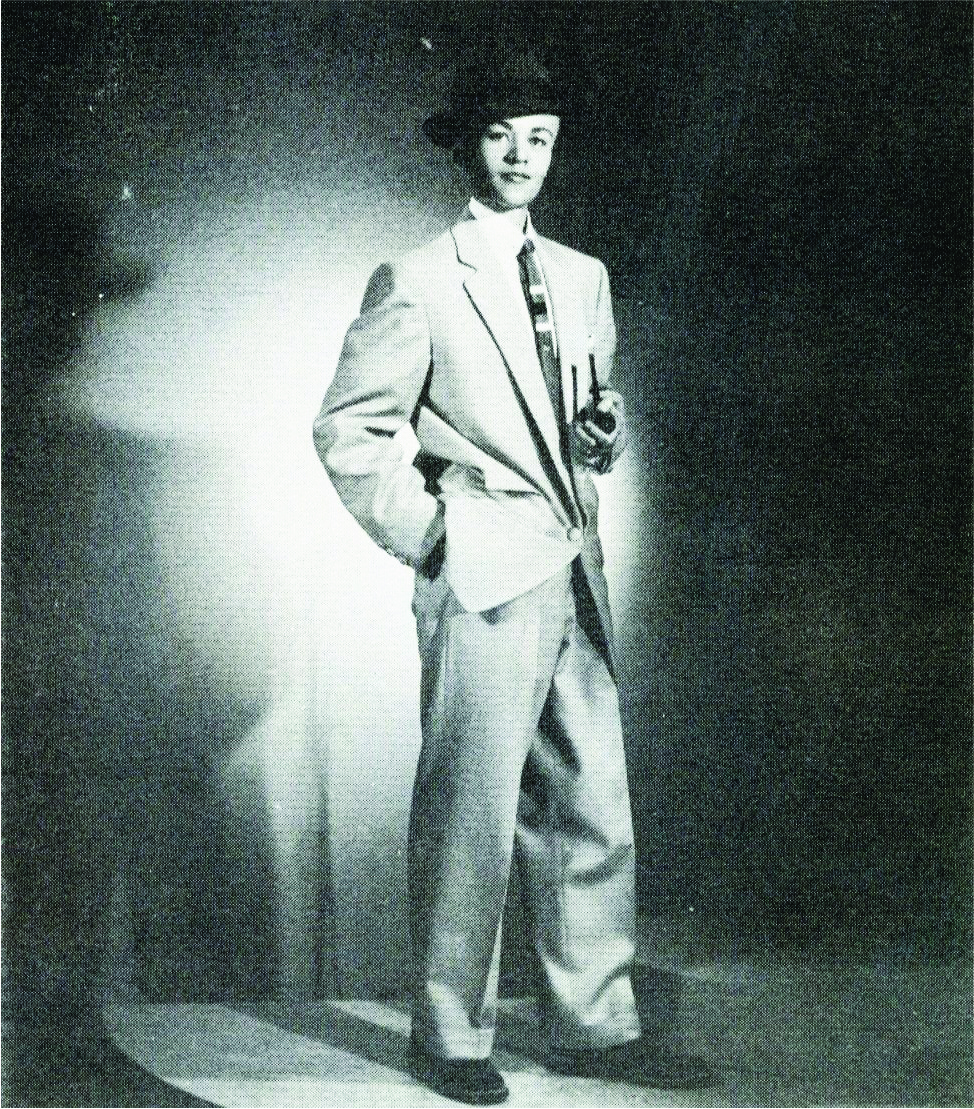

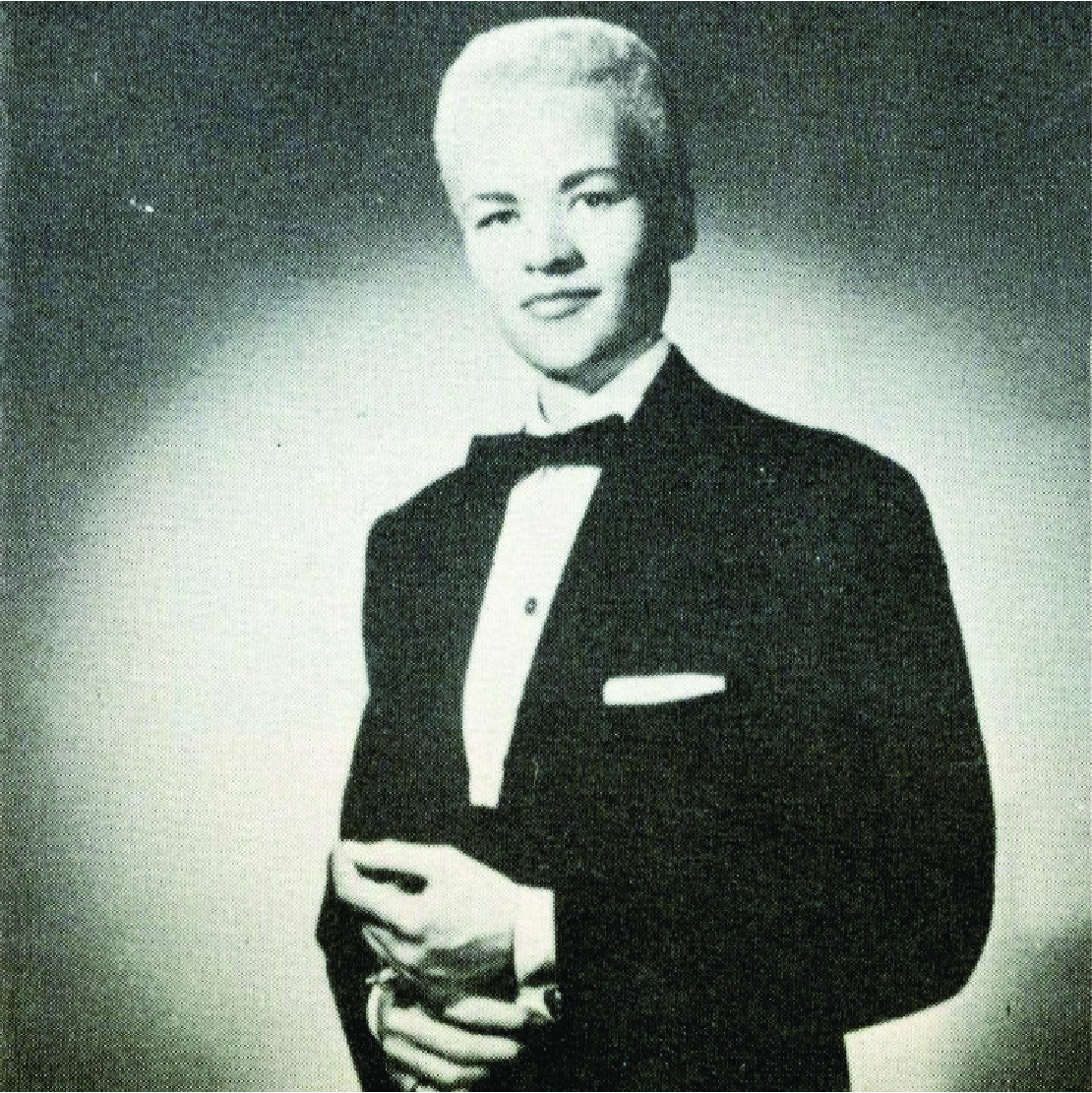

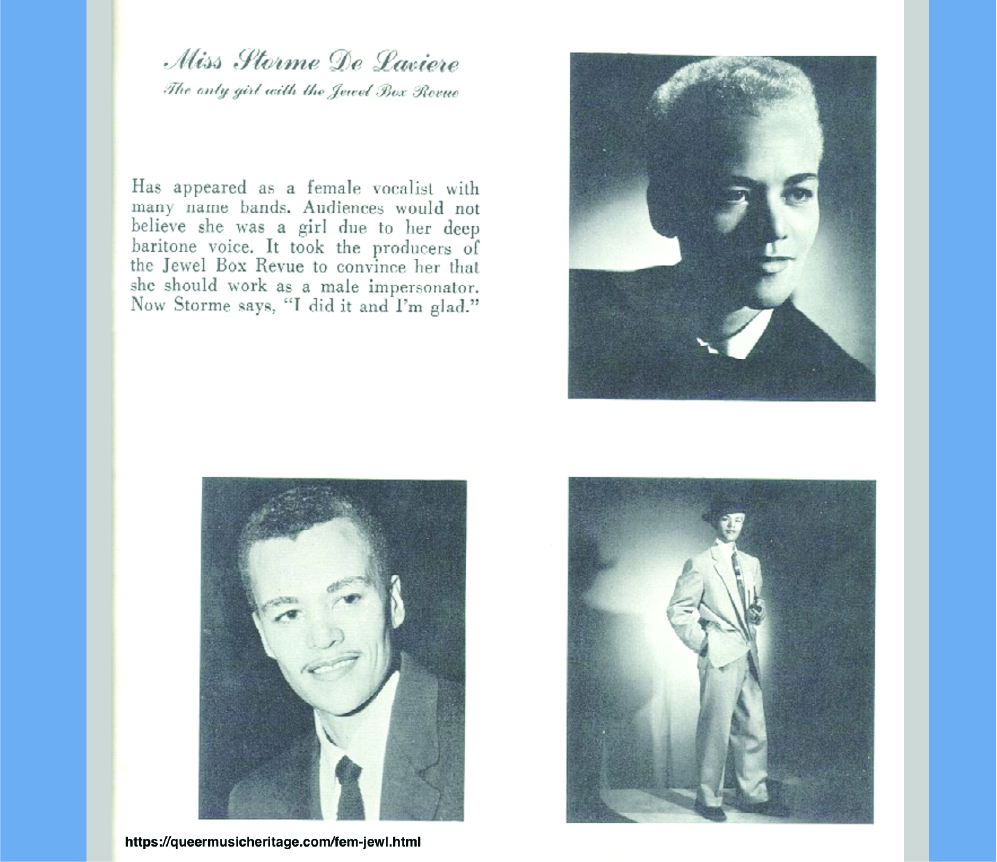

Beginning in 1946, Stormé got her start as a singer with big bands. She wore dresses, make-up, styled her hair in a typical 1940’s manner, and went by the name Stormy Dale. There is evidence of her professional singing career by way of portraits taken by Bloom Photography of Chicago, and from the Jewel Box Revue show programs. In one such program, the description for Stormé reads:

“Has appeared as a female vocalist with many name bands. Audiences would not believe she was a girl due to her deep baritone voice. It took the producers of the Jewel Box Revue to convince her that she should work as a male impersonator. Now Storme says, “I did it and I’m glad.” (7)

The activities surrounding her career from 1946 to 1955, when she started performing with The Jewel Box Revue, are murky at best, and somewhat unknown. She intimated in different interviews that she was in Nebraska, Chicago, and Florida. Who were the many name bands she sang with ? Was she in the Ringling Brothers Circus ? Did she work for the mafia as a bodyguard in Chicago? Did she marry ? Did she have children ?(8) We may never know all of the specific details of her life, but we are certain Stormé had a thriving singing career, had a romantic relationship with a woman named Diana. Little is known of Diana other than that she passed away in 1969, and that Stormé carried Diana’s photo in her wallet for the remainder of her life.

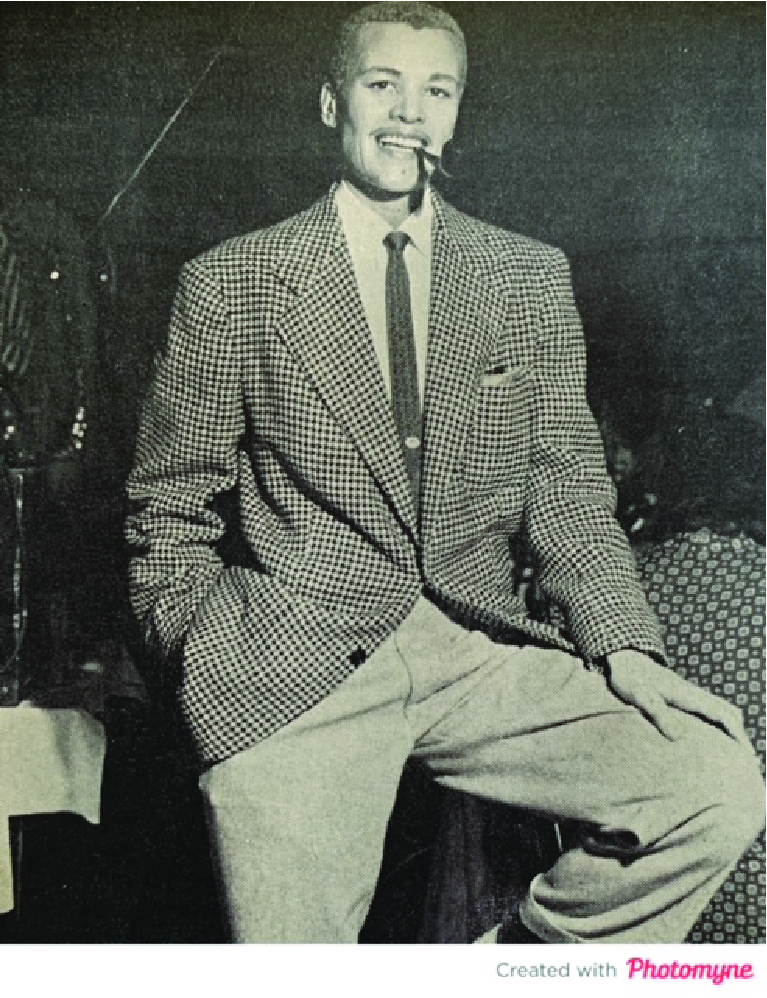

In Michelle Parkinson’s documentary, Stormé: Lady of the Jewel Box, Stormé revealed that in the winter of 1946 on the Venetian Causeway in Miami, she met Doc Brenner and Danny Brown, the founders of the Jewel Box Revue. Becoming a male impersonator in 1955 to perform in their show changed Stormé’s life. She cut her hair short, and began wearing men’s clothing on and off stage. Stormé made a convincing male impersonator as she was tall, lean (so female curves were easily hidden), and had a booming baritone voice that mystified audiences.

Though there is little biographical evidence or documentation of male impersonation from the 1930’s to the 1970’s, Stormé’s presence as the reigning male impersonator fills the void to some extent. We know that Stormé was not the first male impersonator for the Jewel Box Revue; other male impersonators listed in the show programs included Miss Tommy Williams, Miss Mickey Mercer, Miss Jo Vaughn, and Miss Mary “Corky” Davies as the MC’s and “the One Girl”. Hopefully biographical details will emerge to bring light to these women who deserve to be recognized. It is interesting to note, these male impersonators would use the surname “Miss” to protect themselves at a time when cross dressing was a punishable crime, whereas impersonating a person of another gender was considered performance. (9)

Stormé preferred being referred to as a male impersonator, and not as a drag king. In her day, “male impersonator” was considered a more esteemed performance term, whereas the term “drag king” denotes camp, frivolity and exaggeration which Stormé did not embody. (10) And more importantly the term drag king was not colloquially used until the mid to late 1980’s, so to refer to Stormé as a drag king is incorrect. (11) Suffice it to say, Stormé was clearly the most notable and longest running male impersonator for the Jewel Box Revue hence she has been widely recognized over the years.

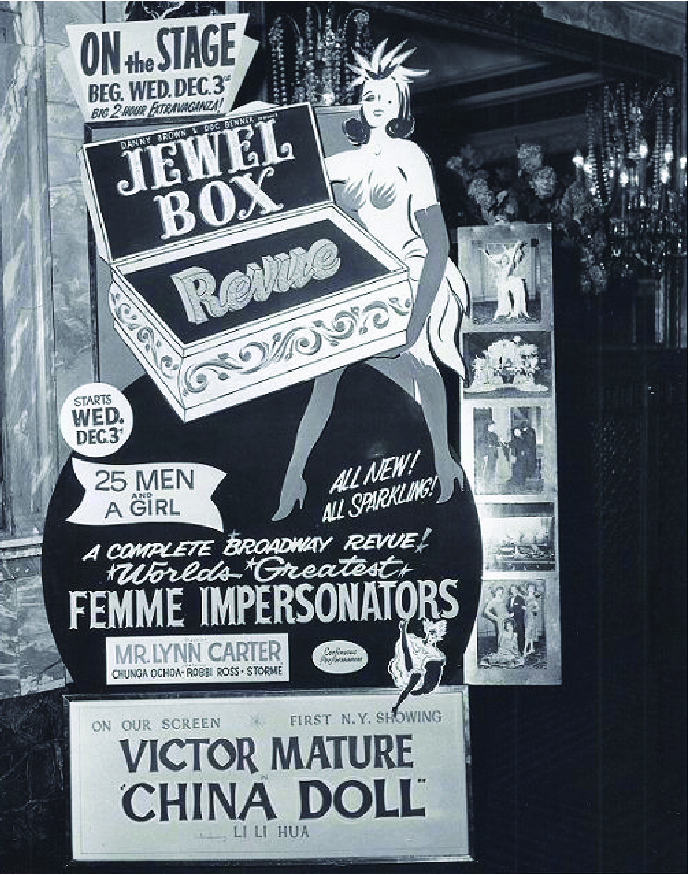

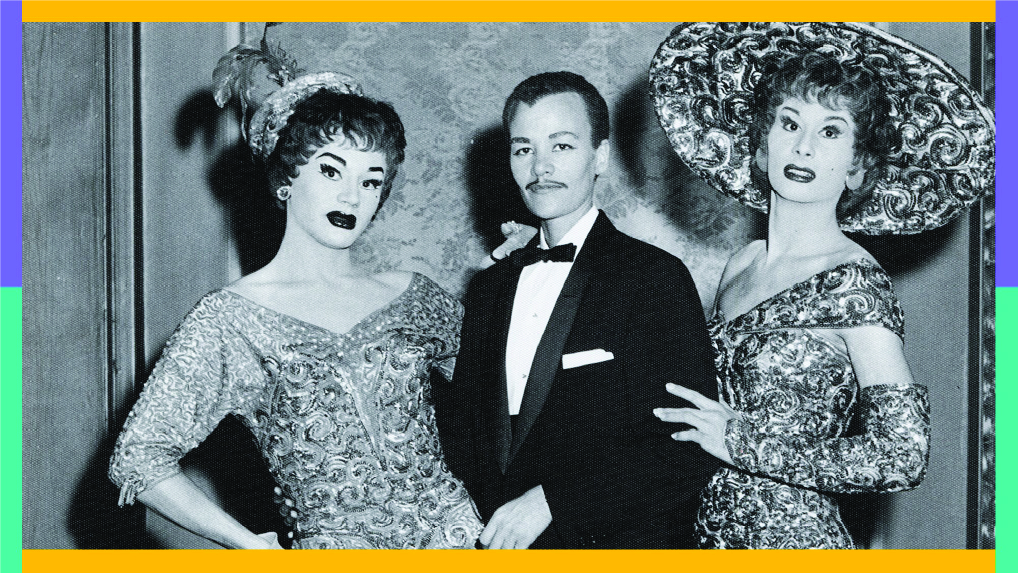

The Jewel Box Revue was first founded in 1939 by Doc Brenner and Danny Brown in Miami, Florida in an effort to “reclaim female impersonation as a legitimate theatrical genre”. (12) The show premiered in 1942 after a wealthy female benefactor provided funding. Billed as “25 Men and A Girl”, the Jewel Box Revue was the first racially integrated, traveling cabaret show that lasted over thirty years. This was at a time when homosexuality and cross-dressing were illegal, and segregation by way of Jim Crow laws along with McCarthyism were widespread and deeply embedded in the American psyche. Doc and Danny created a family show geared for straight audiences in straight venues with an all gay cast. Families thought nothing of men dancing in dresses and a woman singing in a suit. The show was clean, respectable and a spectacle to behold as it was well choreographed and resplendent with feathers, jewels and finery. The Jewel Box Revue toured from coast to coast in North America, and to Mexico and Canada, performing one to three shows a day. They were regulars in renowned nightclubs such as The Apollo Theater in Harlem, The Howard Theater in D.C. The Fox Theater in Detroit, The Shore in Coney Island, and the list goes on. They never lip-synched but sang live accompanied by a thirteen-piece orchestra. This show was the precursor to La Cage Aux Folles, and inspired legions of female impersonators to take root in cities and towns all over the world.

Much of what we know today about the Jewel Box Revue comes from the JD Doyle Archive (13) which includes Danny Brown’s scrap book and various show programs. As the “Girl” in the show, Stormé was the Master of Ceremonies and her duties later included stage manager and musical arranger. Two notable female impersonators have reached out to JD Doyle and shared their experiences in interviews.

Paris Todd said:

“The Jewel Box was not considered drag, but female impersonation. There were 25 men and one woman. The object was to fool the audience into believing we were real women. The real woman was Stormé Delarverie – she sang one song and was the M.C. for the show. Stormé was a great craftsman. When I met her, I thought she was a straight man – perhaps the stage manager? She was always professional and very sweet to me. The show consisted of three production numbers interspersed with the featured acts, chorus numbers and a costume or showgirl parade. At the end we removed our wigs and introduced the real girl.” (14)

Terry Noel who joined the show in 1959 as a female impersonator at the request of Doc and Danny recalls:

“The shows principally centered around lavish production numbers with beautiful costumes and music. Stormé was a real treasure and was so very nice to me when I was a newby female impersonator in Asbury Park.” (15)

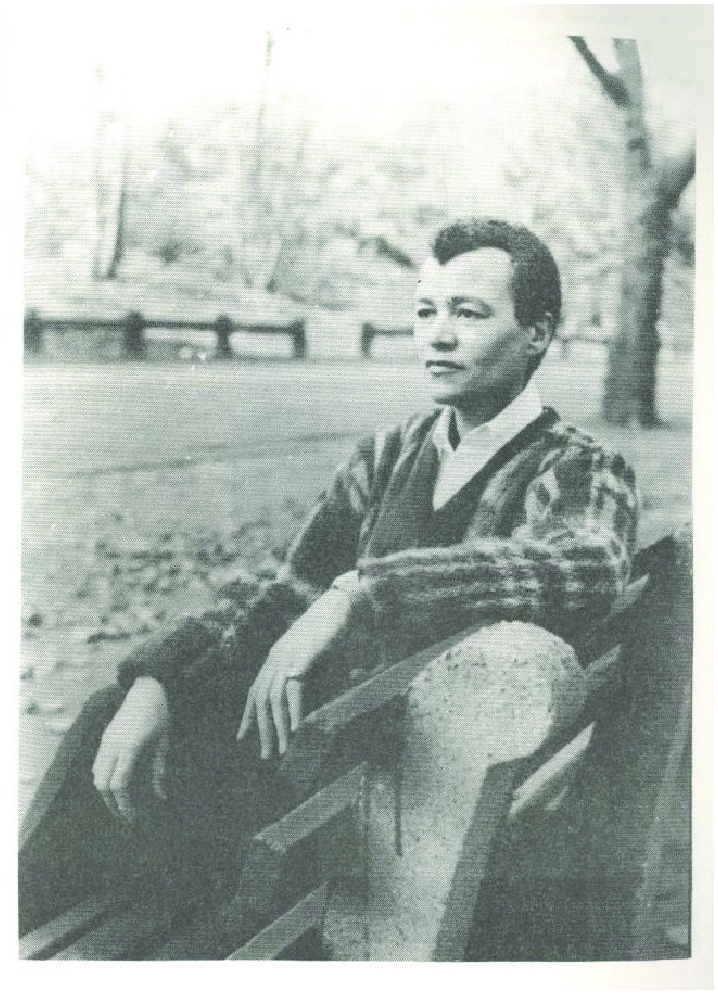

In the late 1950’s or early 1960’s, Stormé befriended well-known American photographer Diane Arbus who took portraits of Stormé in New York City’s Central Park circa 1961. Arbus is best known for her intimate black and white portraits which served to de-stigmatize those who are marginalized in society. These portraits have been widely viewed in museums, books, and documentaries that have showcased Arbus’ vast body of work. (16)

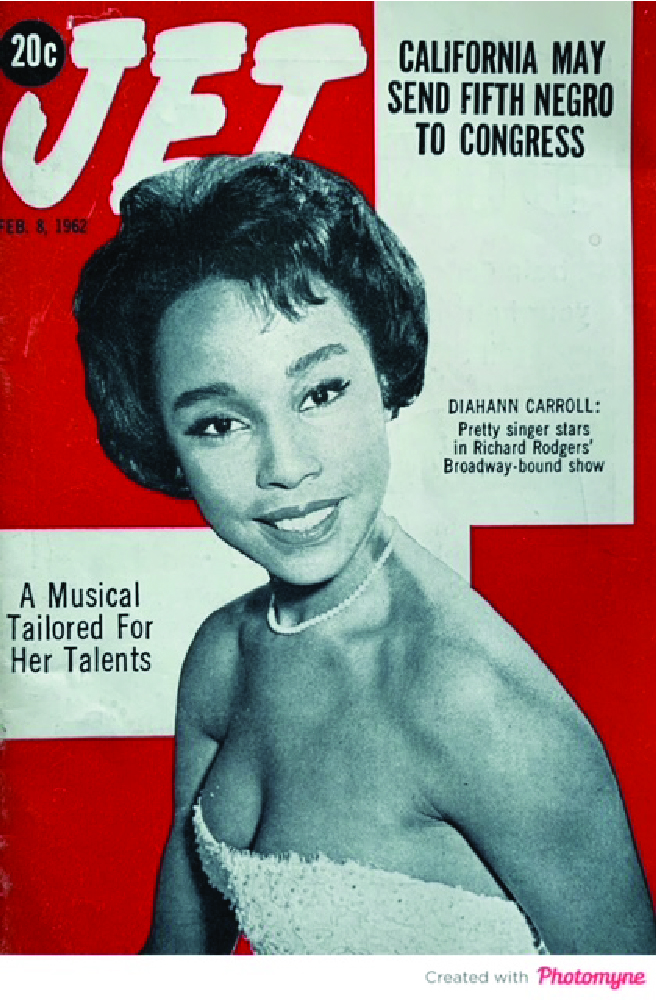

In 1962, Jet Magazine published this short interview with Stormé which lends credence to her marriage:

Mail Mimic Files Suit Against Husband In Calif. (Mr. & Mrs. section, page 23)

Nattily dressed in tight-fitting black pants, high-heeled Spanish dancing boots, a white shirt and a gray golfing sweater, Stormé DeLaverie (see Week’s Best Photos), a crewcut actress and male mimic, walked into Los Angeles Superior Court where she filed suit for an annulment of her nine-year marriage to George S. Freeman, 47, a Chicago air conditioning engineer. The actress, star of Jewel Box Revue, a production in which she is the only woman in the cast of 26, yet the only one who appears to be a man, charges in her suit that she was denied a home, love, affection and children. She said she was married to Freeman on December 24, 1952 at Denver. “ I would just like this marriage to be at an end,“ the actress told Jet. “ I’ve been patient long enough.“ When asked if she planned to marry again, she asserted: “I am not going to give up the idea of marriage. I am sort of thinking about it. But I have to cross one bridge at a time. It would not be fair to either party to announce acceptance or rejection of another suitor until we are free.”

And in the The Week’s Best Photos section on page 32, there is a photo of Stormé taken by Stuart Sutton, and the caption reads:

She Seeks Divorce: Clad in male clothing, for which she has become famed as the only female star of the revue 25 Men And A Girl, Stormé DeLarverie began proceedings to annul her nine-year marriage in Los Angeles, where the revue is currently playing (see Mr. and Mrs.). (17)

There are so many questions unanswered, but at present, this is all that Drag King History knows of Stormé’s marriage to George S. Freeman.

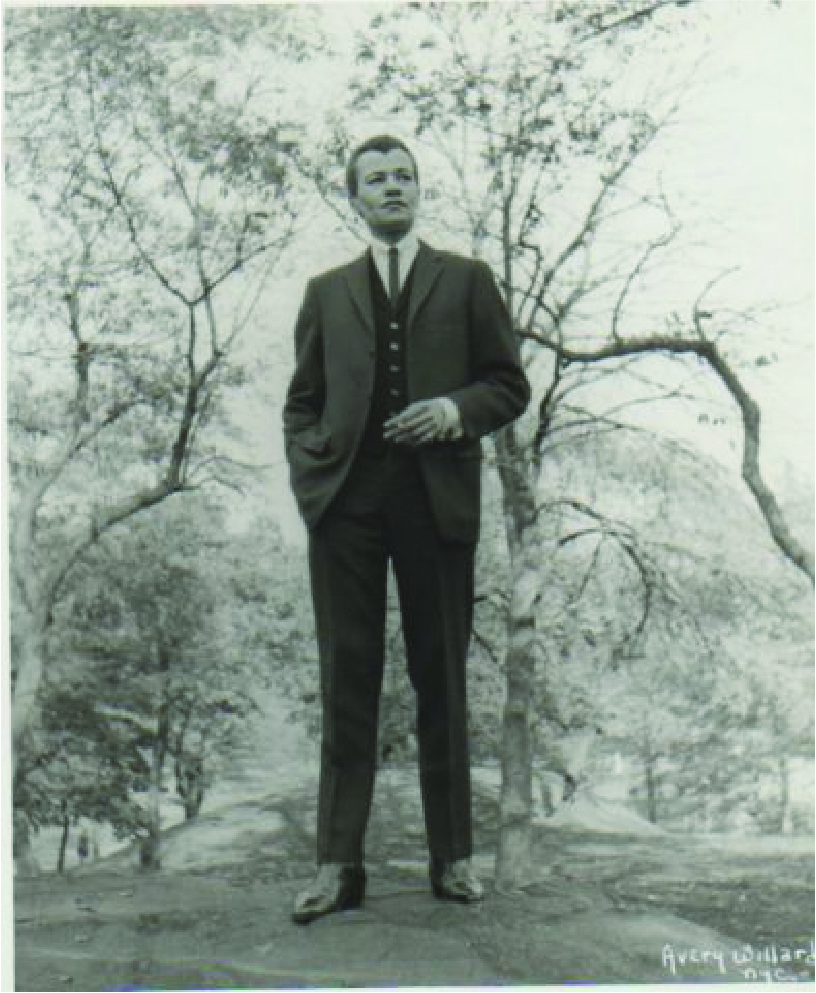

In 1971, Avery Willard published his book Female Impersonation. (18) Willard included biographical sketches of numerous female impersonators and Stormé much like the Jewel Box Revue’s billing as “25 Men and A Girl”. He wrote that Stormé “now always dresses like a man”, and is constantly mistaken as a man. When asked whether she preferred to be called he or she, her reply was, “whatever makes YOU feel the most comfortable.” (19) Willard states in the interview that her grocer thinks she’s a man but her tailor knows she’s a woman. He photographed Stormé in the mid to late 1960’s in his studio and in Central Park.

Stonewall – from June 28th to July 3rd of 1969, a rebellion occurred that proved to be the point of no return for the LGBT community. What actually happened and who was the catalyst for the uprising has been mythologized for years. Over the years, there have been inconsistencies in stories and myths conjured to reclaim personal identification to its history. Author David Carter wrote what is widely considered the definitive history of the Stonewall uprising. He did extensive research for his book, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution, and came to the conclusion that Storme DeLarverie was not the lesbian who instigated the riots.

David Carter writes “To cite a few problems with this thesis (Stormé threw the 1st punch to ignite Stonewall), DeLarverie’s story is one of escaping the police, not of being taken into custody by them, and she has claimed that she was outside the bar, “quiet, I didn’t say a word to anybody. I was just trying to see what was happening,” when a policeman, without provocation, hit her in the eye (“Stonewall 1969: A Symposium,” June 20, 1997, New York City). DeLarverie is also an African-American woman, and all the witnesses interviewed by the author describe the woman as Caucasian. Finally, there has been much speculation about who this woman could have been, what we know is a lesbian did play a key role. Stormé was well-known in the local lesbian community at the time of the riots and has remained so ever since, and it is highly improbable that this woman who was seen by hundreds of people could have been a person of note in the community, else she would have been identified at the time or shortly thereafter.” (20) As Carter stated, Stormé’s stories were inconsistent and changed over the years. She was later diagnosed with dementia lending further question into the veracity of her stories.

There is further evidence to refute the claims that Stormé was the lesbian who instigated the rebellion. Firstly, by all accounts, there is no known evidence of any woman throwing a punch especially to a police officer as this would have been recorded by the police. We do know that a butch lesbian resisted arrest, probably had the greatest impact, and her identity remains unknown. (21)

The story that Stormé threw the first punch, was most likely attributed to Stormé as her contributions to the LGBT community are undeniable. She was loved by many, respected as an elder, became an endearing icon, and remained an inspiration as a staunch protector of LGBT folks.

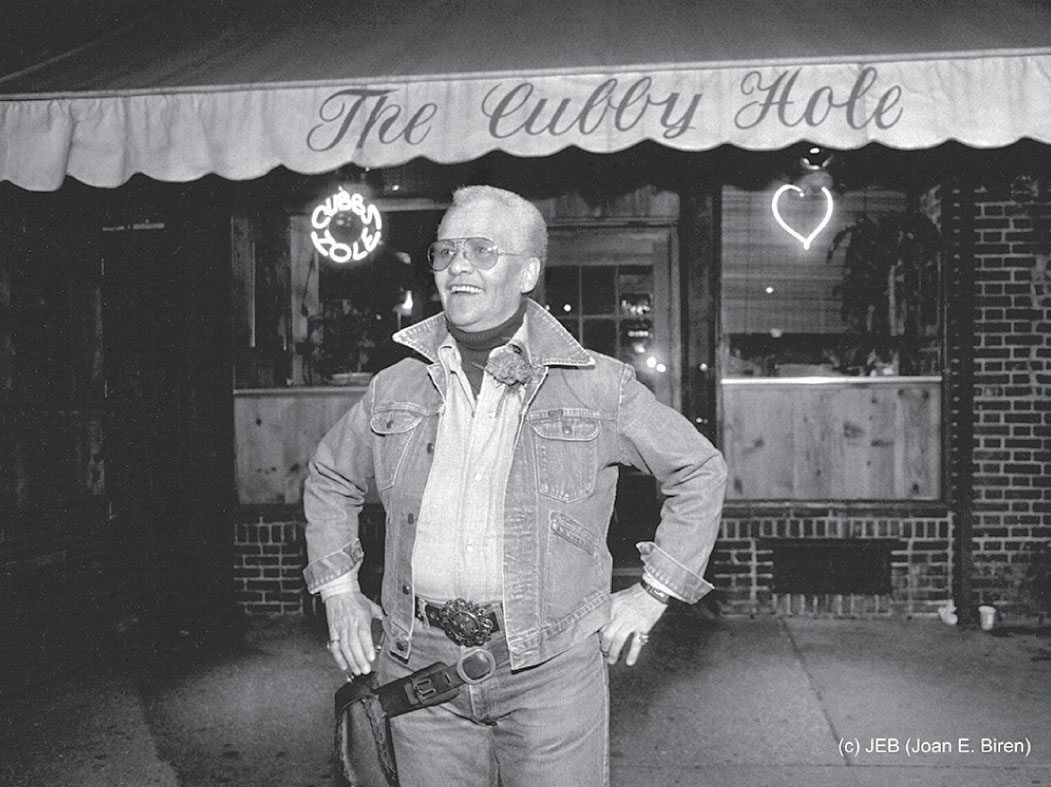

In September 1969, Stormé left the Jewel Box Revue after Diana, her lover of 26 years, passed away. It’s not clear nor known where she worked during the 1970’s. Beginning in the 1980’s through to 2005, she made her living working security at neighborhood lesbian bars the Cubby Hole and Henrietta Hudson in the West Village. But that didn’t limit her as she would roam the streets of lower Manhattan “on the lookout for what she called “ugliness”: any form of intolerance, bullying or abuse of her “baby girls.” (22) If anyone anywhere was in need, she’d be there. She did this well into her 80’s until dementia, old age, legal and housing issues troubled her.

Stormé was a resident of the famous Chelsea Hotel and lived there from the 1970’s until 2010. Many long-time residents fought to keep their apartments, but the new owners of the Chelsea Hotel in 2008 began to make their stay untenable. From 2010 to her death in 2014, Stormé resided in nursing homes in Brooklyn.

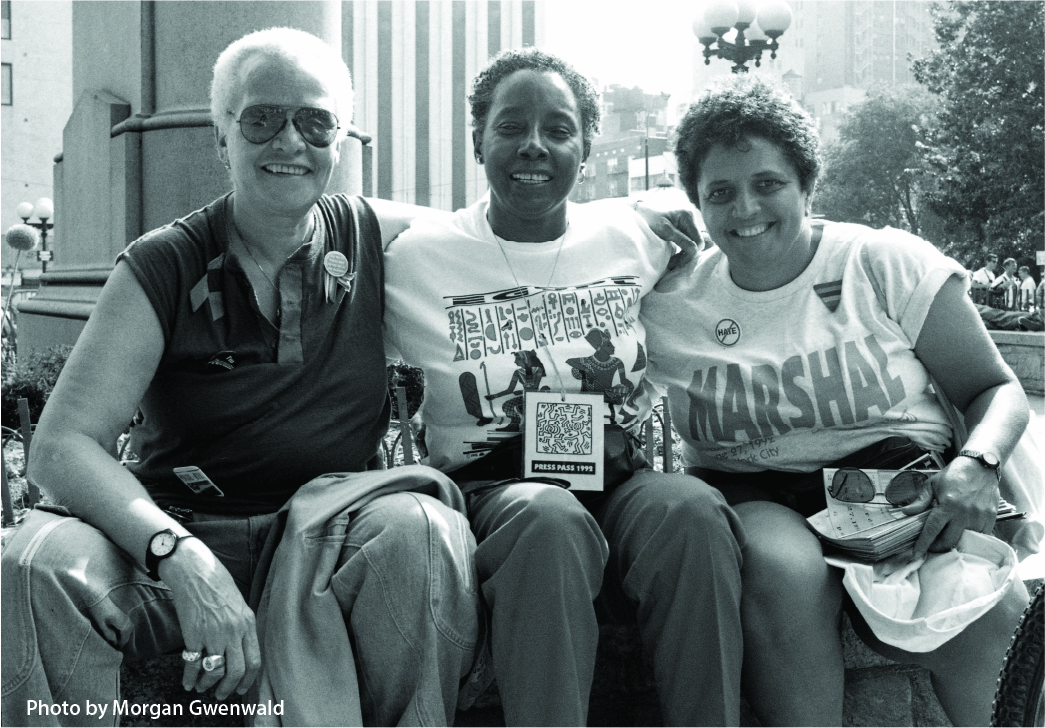

She was a member of The Stonewall Veterans Association, and walked in numerous New York City Pride parades with them. She served as a member of The Imperial Queens and Kings of New York commonly called I.Q.K.N.Y. where annual proms were held at the LGBT Community Center 208 West 13th street in Manhattan. In 2000 she was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by SAGE.

Stormé DeLarverie passed away on May 24, 2014 in a nursing home in Brooklyn, New York. She lived her public life privately so we may never know all the specific details of her life. One of her well-known sayings was “It ain’t easy being green.” (23) Drag King History salutes one of the greatest male impersonators of all time.

(Submitted by Mo B. Dick, Los Angeles, CA)

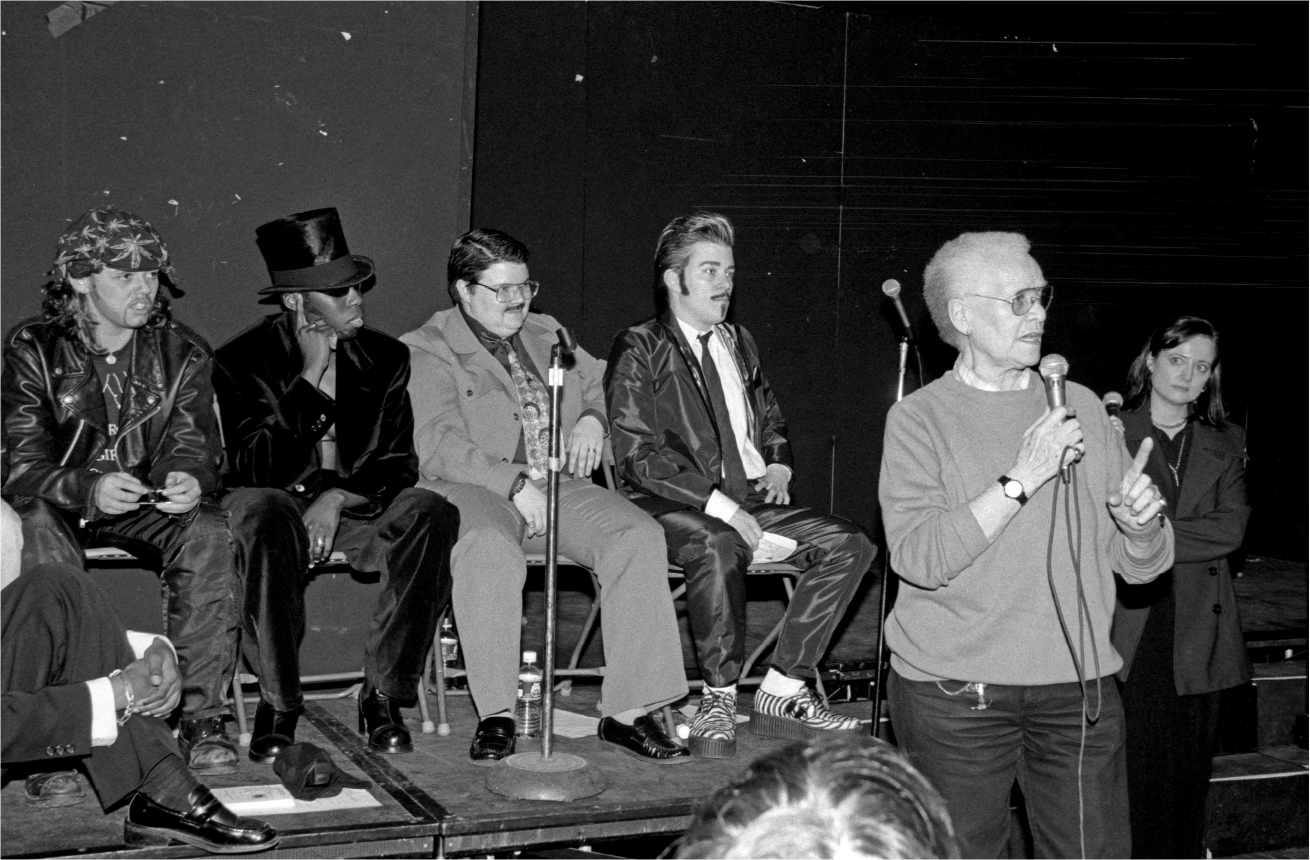

1997 LGBTQ+ Community Center: Stormé Delarverie on mic with NYC Drag Kings from R to L Mo B. Dick, Murray Hill, Dred, Michelley, and filmmaker Lucia Davis behind Stormé photo by Efrain Gonzalez

1997 LGBTQ+ Community Center: Stormé Delarverie on mic with NYC Drag Kings from R to L Mo B. Dick, Murray Hill, Dred, Michelley, and filmmaker Lucia Davis behind Stormé photo by Efrain Gonzalez